OK, Chicken Little: Why The Opposite Of Climate Action Isn't Denial, But Apathy

The most harmful lie told about climate change isn't that it's a hoax, but that it's not that bad. It's a narrative that serves only those who profit from destruction.

This is Edition #12 of The Climate Laundry. Please become a paid subscriber if you find my work valuable and you have the means.

In a world increasingly shaped by the way people talk to one another online, earnestness has been made a vice, and apathy a virtue. This has lethal implications for climate action.

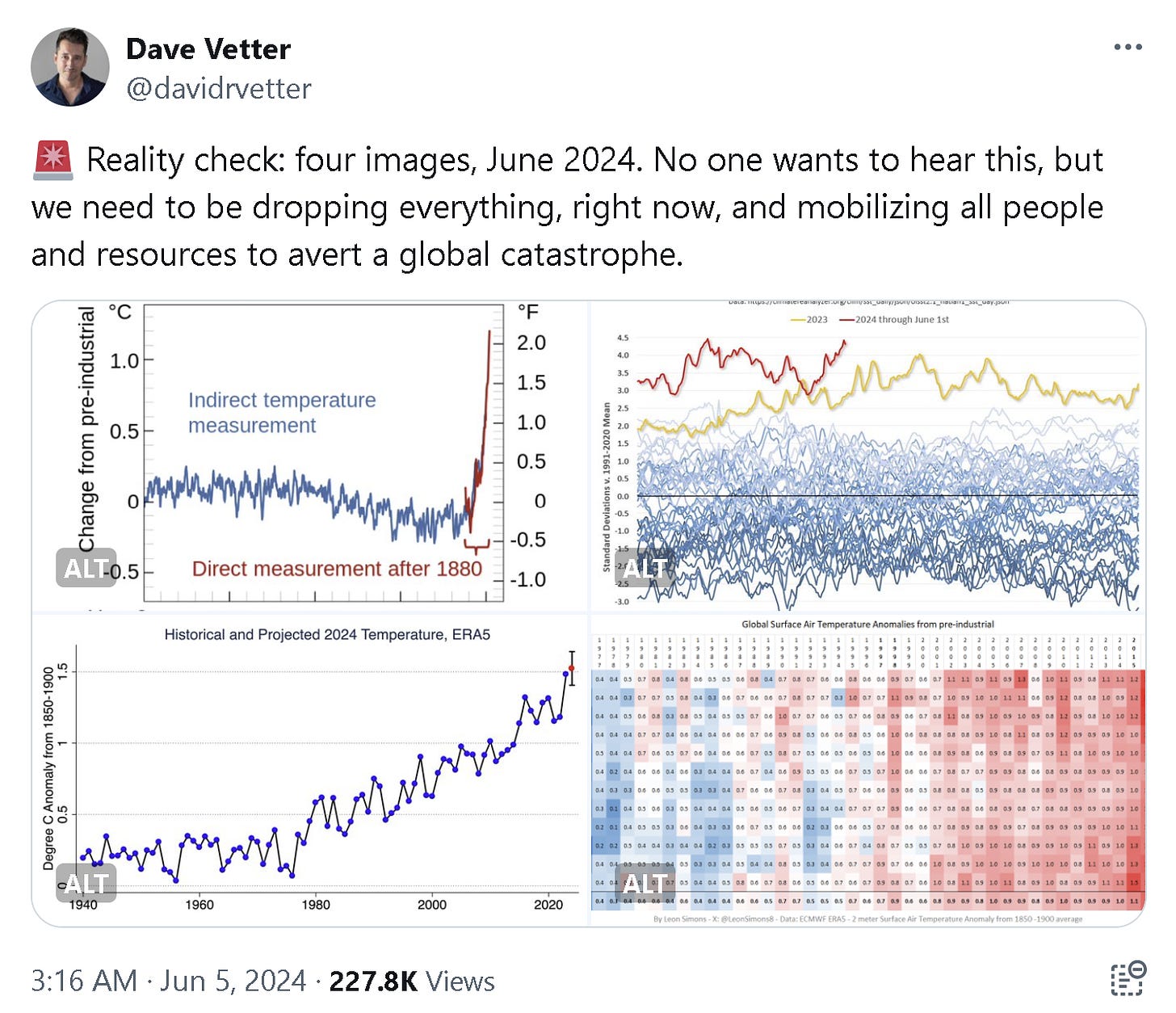

I was reminded of this calculus earlier this month, when I made an impassioned climate post on The Website No One Calls X. Dropping in some well-known charts showing CO2 and temperature increases across a range of timescales, I tweeted: “Reality check: four images, June 2024. No one wants to hear this, but we need to be dropping everything, right now, and mobilizing all people and resources to avert a global catastrophe.”

I don’t usually post in such dramatic terms, but on viewing the latest temperature chart updates from Zeke Hausfather, I had felt moved to do so. I also knew that emotive posts on social media are massively more likely to engage people than intellectual ones.1

The post elicited a great deal of interest, along with a chorus of derisive hooting from the internet’s low-information peanut gallery, who informed me that, actually, climate change is a hoax. That’s okay: science denialism is rapidly becoming mandatory on the site also known as Elon Musk’s Eugenics Blog, and besides, I no longer engage with such people directly. Arguing with internet nobodies is like competing in a bake-off with a beagle: the only one who stands to gain anything is the beagle.

This doesn’t mean, however, that such claims shouldn’t be analysed, albeit in the confines of a virtual “clean room”. After all, such disinformation is causing real-world harms. While climate deniers (shorthand for people who claim that human-caused global warming isn’t taking place) comprise a small minority of the population,2 their online activity, backed by the fossil fuel industry, is causing people to believe that climate change isn’t as big an issue as the news media makes out.3 That’s concerning, as the news media doesn’t make climate change out to be a big issue. Climate denial, then, operates like the radical flank effect, inverted to serve the status quo.

Numbed into ambivalence and even apathy, these climate dismissives, who discount the need for urgency of action, comprise a far larger segment of the population than do deniers. The prevalence of this dismissiveness is laid bare in a new Yale study of US voters ahead of the November elections, in which climate ranks a dismal 19th out of 28 issues that registered voters prioritize.4

And that’s why it is dismissives, and dismissive narratives, that pose the most critical threat to implementing serious climate action.

The Dismissive Norm

Climate deniers foster climate dismissiveness through plausible, sciencey-sounding slogans. These include tropes like “CO2 Is Plant Food”, which takes the fact that plants need CO2 to thrive, and leaps heroically to the conclusion that excessive greenhouse gas emissions is good for plants and, consequently, us. Another device, whataboutism, is deployed through quasi-rhetorical questions like “What About China?”, which handily ignores the fact that China is a world leader on decarbonisation.

Such examples of conventional climate denialism may sound reasonable to regular people. They help enable a broader ambivalence about climate change that leads to claims—both online and offline—that climate communicators are being “alarmist” when they talk of impending crises. The refrain du jour, according to my Twitter replies, is “Ok, Chicken Little”, evoking the folk tale of the irrationally frightened bird who believes the sky is falling.

As a put-down, Ok, Chicken Little is curt, funny and requires essentially no effort on the part of the poster. It’s also effective. As shown by author Genevieve Guenther in her forthcoming book The Language of Climate Politics, reviewed in this newsletter: “… the discourse of alarmism functions like a network connecting disparate ideological groups. Those on the right who would deny that climate change is real are connected to centrist techno-optimists who acknowledge its reality but deny its dangers.” There are also those who believe that, even if multiple tipping points are on the way, there’s nothing anyone can do about it. Summarising this sentiment, one respondent recommended that I “kick back, open a cold one, and watch it all fall apart.” In all cases, the net effect is the same: society at large rejects the idea that urgency is required.

In reality, the fable of Chicken Little offers a polar opposite to the warnings of climate scientists. The fearful fowl’s irrational panic upon being hit on the head by an acorn arises from having too little information. The global scientific community, on the other hand, is being wholly rational when it warns that the stable conditions we rely on for our food, water and safety are quite simply going away, and what's more, we're causing them to go away. This isn’t a “panic” born of too little information—it’s a concern informed by attending to everything that the physical sciences are telling us.

Unfortunately, in this cultural moment, telling people they’re being alarmist ticks a lot of desirable, comforting boxes. While, per The Fonz, being cool has long been synonymous with not caring too much about anything in particular, the internet simply cannot abide earnestness. As scholar Whitney Phillips has shown in her books This Is Why We Can't Have Nice Things and The Ambivalent Internet (co-authored with Ryan Milner), online culture has, to a horrifying extent, made sincerity and selflessness taboo. In our new upside-down, a world in which public life is increasingly defined by opinions on the internet, earnestness is the most embarrassing vice of all. Suggesting humans can do better, should strive, and do have agency is, then, a cardinal sin. Telling someone to “kick back, open a cold one, and watch it all fall apart” is not just the last word in nihilistic apathy, it’s a shield that protects you against charges of enthusiasm, earning you online cool points.

Bursting The Unreal Bubble

Given the prevailing economic winds of the late 20th century, such an outcome was predictable. Neoliberalism’s tenet that there is no such thing as society, only self-interested actors, was a self-fulfilling prophecy. Writers such as Ece Temelkuran have observed that at least a degree of apathy is necessary to endure the rampant inequalities that neoliberalism fosters and indeed depends upon. The endlessly cynical denizens of online are, from this perspective, simply being good little consumers.

This, then, is why unstructured ambivalence and dismissiveness are more dangerous than conventional climate denial. In our unreal world, in which we’re continually incentivised to ignore a civilisation-scale crisis, apathy simply swims with the social, cultural and economic tides, both actively and passively reinforcing the status quo.

So what is to be done? Much has been written about how to break this self-perpetuating cycle. The brutal truth, which climate communicators and scientists still grapple with every day, is that people don’t care about facts, they care about things that reinforce their preconceptions. Or to put it in the words of psychological science professor Peter Ditto, “truth is really a team sport”.

This being the case, a shift in the fabric against which our lives play out is required. And that requires cultural change. “Culture anchors people to places and to each other,” notes the European Network of Museum Organisations. “It creates cohesion in unique ways: enabling community-building and collective action, providing shared moments, feelings and commitments, inventing new symbols and new tools.”

Crucially, culture has the ability to inspire and elevate ambition. This is what novelist Amitav Ghosh meant when he wrote that “the great, irreplaceable potentiality of fiction is that it makes possible the imagining of possibilities.” That means going much further than imagining a world ruined by climate change—we need to envisage positive futures in which humanity has risen to the challenge of building a safe, just and meaningful existence.

As the work of climate story advocate Anna Jane Joyner has shown, the near-comprehensive failure of our entertainment, our books, our films and our games to acknowledge climate change makes it far easier to be a climate dismissive. A culture that instead acknowledged climate change would help establish a phenomenal baseline that would make climate dismissiveness seem absurd. That’s why Joyner’s non-profit Good Energy, along with Maine’s Colby College, have developed a test that asks whether a movie 1) acknowledges that climate change exists and 2) whether a character in that movie knows it. Of 250 popular films from 2013 to 2022, only 9.6% of were found to have passed the test.

Of course, a tool that looks at movies only covers a tip of the iceberg of a subset of popular culture. But it’s a laudable effort that dare us to ask why our cultural diet continues to evade the physical context in which we live.

When I recently asked the author Mary Annaïse Heglar whether she thought more climate fiction would help shake off society’s collective climate apathy, her response was instructive: “We don’t need climate fiction,” she said. “We just need our fiction to reflect reality.”

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666061X21000924#

https://news.umich.edu/nearly-15-of-americans-deny-climate-change-is-real-ai-study-finds/

https://counterhate.com/research/new-climate-denial/

https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/climate-change-in-the-american-mind-politics-policy-spring-2024/toc/3/