'Star Wars Without Darth Vader': It’s Time We Named The Causes Of Climate Failure

Our media are great at identifying the symptoms of climate inaction, but hopeless at naming its architects. A new book shows there's no excuse for such ambiguity.

This is Edition #13 of The Climate Laundry, released early owing to travel commitments. Please become a paid subscriber if you find my work valuable and you have the means.

“We live in an age of fools.”

This succinct indictment of our era, from an anonymous climate researcher, was included in a Guardian article in May. The paper had surveyed 380 climate scientists for their views on where the world was heading, and none of it was good news. Another scientist quoted said they felt “helpless and broken”.

But in an accompanying article on why researchers are feeling this way, things got a little strange. “The experts were clear on why the world is failing to tackle the climate crisis,” the article ran. “A lack of political will was cited by almost three-quarters of the respondents.”

This is puzzling, not least because “lack of political will” doesn’t really mean anything—or rather, in the climate context it’s so nebulous as to be meaningless. Justice reform expert Linn Hammergren has described political will as “the slipperiest concept in the policy lexicon … the sine qua non of policy success which is never defined except by its absence.” Or as political consultant Mark Funkhouser has explained: “Political will is not some kind of immutable and innate personal quality … It is a deliberate social construct, and every positive advance of public policy rests upon its successful creation.”

So why did it show up here?

It turns out that “Political will” was one of nine possible answers The Guardian offered to scientists in response to the question: “What do you think the biggest barriers are to halting and reversing global heating? Is it a lack of:”

Now, this isn’t going to be an essay about sloppy research methodologies or manipulative question design. But it’s worth asking why The Guardian chose to frame a keystone question about climate inaction in such a way that the answer would reveal nothing.

As luck would have it, a new book offers an explanation as to why experts perceive a “lack of political will” among elected leaders. Furthermore, it offers clues as to why our media seem unable to explain what’s going on.

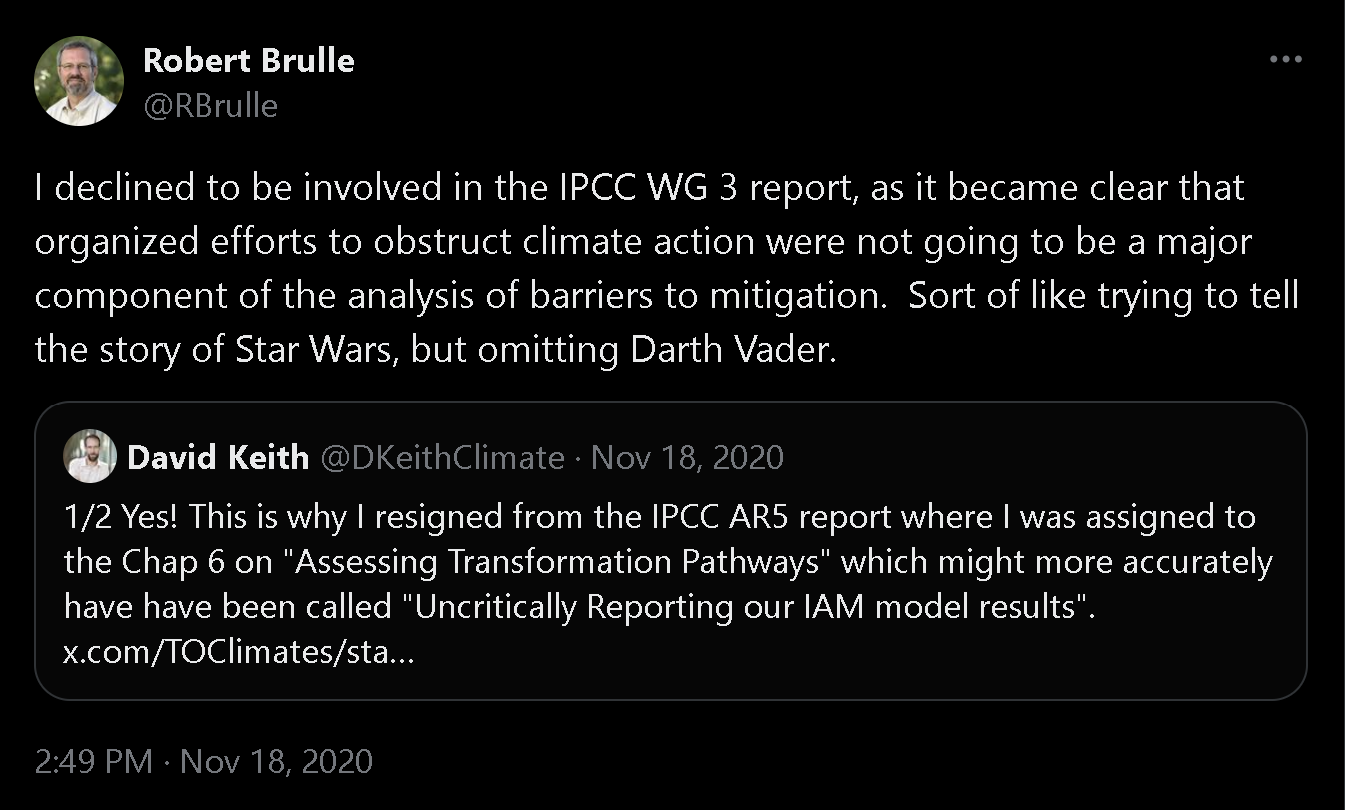

In Climate Obstruction Across Europe, social scientist Robert Brulle and colleagues have brought together a dozen studies identifying the forces that have blocked climate progress on the continent. Among his achievements, Brulle is known for being the guy who said that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was in effect “trying to tell the story of Star Wars, but omitting Darth Vader” when it chose not to include analysis of organized efforts to obstruct climate action in its Summary for Policymakers.

In their book, Brulle and co-authors expand authoritatively on this criticism, with individual profiles of 12 different European nations and regions, from Scotland to Russia. In each instance, they paint a portrait of who is carrying out climate obstruction, why they’re doing it, and how those actors have been so successful. The authors show that climate obstruction is organised, nuanced and complex—while at the same time being far more tangible and objective than vague speculation about “political will” might suggest.

Take, for example, the book’s chapter on the UK. In it, researchers Freddie Daley, Peter Newell, Ruth McKie and James Painter offer a summary of Britain’s climate progress, about which there is much to be commended, but subsequently show how the calamitous Brexit project was used by key actors to further the climate obstructionist agenda, with the backing of fossil fuel interests in the United States in the form of Atlas Network lobby groups. They name British individuals such as businessman Jeremy Hosking, whose company holds hundreds of millions in fossil fuel investments. They call out specific government departments, media organisations, trade associations and even unions that have taken every opportunity to kill off policies that might otherwise enable a route to net zero. The chapter concludes by offering key interventions that could help weaken the power of obstructionist groups, including new rules governing the transparency of political donations, and subjecting “revolving door” relationships between government, business and media to greater scrutiny.

Next, compare and contrast the situation in the UK with that of Ireland. In their chapter, Orla Kelly, Brenda McNally and Jennie Stephens show that the Republic’s agriculture sector wields disproportionate power in policymaking circles, and intense lobbying from agri-food has consistently presented climate policies as being a material threat to the sector. Meanwhile, over in the Netherlands, Martijn Duineveld, Guus Dix, Gertjan Plets, and Vatan Hüzeir show how oil giant Shell “has a special place in Dutch climate obstruction due to its strong historic links to politics and society”. The firm is able to exercise its obstructive might at every level of society, via direct political access, intense lobbying, and overwhelming marketing drives in schools, universities and cultural institutions. In each chapter, the authors make sure to name the individuals known to have had a leading role in either funding or spreading climate misinformation, such as Ray Bates and Jim O’Brien in Ireland, and Frits Böttcher and Guus Berkhout in the Netherlands.

In short, the book describes how the forces orchestrating climate obstruction possess significant regional differences in motivation, with strategies tailored to each nation. Yet many of the actors identified share common, often well-funded networks; the through-lines are clearly visible. The book shows conclusively that, when politicians are said to “lack the political will” to push for or support climate action, it is because they have been coerced, co-opted or otherwise influenced by a discrete set of specific actors to take a specific set of actions. To assign the blame for inaction to an abstract non-entity is not simply to fail in identifying the problem—it directly abets those bad actors.

Climate Obstruction Across Europe is all the more valuable in light of the preoccupation in the research literature and the media with the influence of the United States. While the book acknowledges the malign involvement of the powerful network of US-funded fossil fuel “think-tanks”—which operate in most European nations—it clearly shows that these organisations aren’t central to obstructionist activity, instead helping to amplify and coordinate existing obstructionist causes.

In convincingly revealing the who, how and why of climate obstruction, Brulle and co’s book indirectly pops the lid off our media’s general inability to effectively do the same. While some outlets and journalists have gone beyond the call of duty in unmasking those bad actors, efforts to systematically outline those activities and networks of influence have been thin on the ground. More to the point, when stories about climate inaction surface, they seldom connect the dots between cause and effect.

This takes us full-circle to Brulle’s complaint about the IPCC not surfacing climate obstruction in its summary. While such relevant information is included in the body text of the full reports, the fact is that most journalists will never find it (2023’s AR6 synthesis alone was 8,000 pages long). This, Brulle and colleagues write, is not an accident. While the IPCC’s experts are not political actors, the IPCC’s reports are “vetted by nearly every government on Earth” and “frequently watered down, with key text struck from the final document before publication”. As researcher Kari De Pryck has commented, this means that the Summary for Policymakers, which offers key, actionable takeaways, “tends to construct climate change as a decontextualized and nonpolitical problem.”

This is, self-evidently, a major problem. To quote the plethora of great thinkers credited with the phrase, everything is politics. When shorn of context and political considerations, no climate issue can be dealt with, least of all climate obstructionism. When the global authority on all things climate change avoids talking about the who and how of why we’re unable to do much of anything about climate change, it makes it fiendishly difficult to form an understanding of the problem and how to solve it.

Climate Obstruction Across Europe concludes with 10 lessons about the topic which, to put it in the mild language of the book, carry “extensive policy implications”. One very salient finding is that, on matters of climate obstruction, the power of public opinion has been overestimated, and is not an effective leverage point for enacting change. Much like “political will”, public opinion isn’t some abstract and unknowable force—rather, it is curated and crafted by distinct actors: to paraphrase Aldous Huxley (or possibly Edward Bernays), people want what they’re given. A better use of resources, the authors suggest, would be to do what the forces of obstruction do so effectively, which is to focus on “swaying key players”, such as legislators.

The upshot of all this is that, as the world heats up, we can’t say we don’t know why we’re not making quicker progress on climate mitigation. To paraphrase singer Utah Phillips: “Climate action is not dying, it is being killed. And those who are killing it have names and addresses.” We know who they are, and we even have a pretty good idea of how to counter their efforts. We have to say as much, and act appropriately.

Ours will remain an age of fools just as long as we allow ourselves to be fooled.

Needless to say, Climate Obstruction Across Europe contains more useful takeaways than I can hope to cover here, so I recommend you download it here (it’s free!).

Elsewhere in climate news …

I wrote a big fat article for Forbes on the Oxford-led State of Carbon Dioxide Removal report. The report is actually an update to last year’s original, and this time around includes lots of important extras, including an analysis of carbon removal pathways consistent with UN Sustainable Development Goals on things like hunger and access to energy. If my social media feeds are anything to go by, carbon removal is only getting more controversial. But the authors of the report make the point that while carbon removal offers ample room for moral hazards, greenwashing and getting it all terribly wrong, the tech is none the less indispensable for achieving net zero or indeed net negative CO2, which is where we need to be. (Forbes)

Austyn Gaffney at the New York Times covered a study in Nature Ecology & Evolution that shows extreme wildfires have doubled in intensity and frequency over the last two decades due to climate change. Lead author Calum Cunningham, a postdoc in pyrogeography at the University of Tasmania, explained that most fires are “relatively benign and in most cases ecologically beneficial” but that “such a big increase over such a short period of time makes the findings even more shocking. We’re seeing the manifestations of a warming and drying climate before our very eyes in these extreme fires.” The piece notes that wildfires are now costing the US up to $893 billion every year. (New York Times)

Tom Phillips in The Guardian has a stunning feature on a Brazilian special forces operation to take out the mining gangs that are destroying the Amazon rainforest in Amazonas state. The offensive took place on the second anniversary of the murders of Brazilian indigenist Bruno Pereira and British journalist Dom Phillips. Beyond protecting the rainforest itself, one official from Brazilian environment protection agency Ibama tells Phillips that, without government help, “we will inevitably witness an ethnocide” of the indigenous people of the Javari valley. (The Guardian)