UK's Climate Election: Labour Must Rise Above The Politics Of Despair

When our politicians say "better things aren't possible", people believe them. Instead of feeding the downward spiral, Britain's presumptive leaders can inspire a battered nation by telling the truth.

This is Edition #11 of The Climate Laundry. Please become a paid subscriber if you find my work valuable and you have the means.

Can Britain dare to dream—or can it afford not to?

Those who live elsewhere might be unaware that the UK has a national election coming up. It’s scheduled to take place on July 4, and most polls suggest that the incumbent Conservative party, which has been in nominal charge since 2010, is set to be power-hosed out of office.

That’s a good thing. In those 14 years, the Tories have chewed through five prime ministers, each of whom has attempted, with varying degrees of success, to stamp his or her house brand of fecklessness, corruption and mindless cruelty onto the country. An exhausting cavalcade of posh sub-mediocrities has engineered a crushing, downward spiral of immiseration, inequity and hopelessness that feels, to many, inescapable. The very notion that Britain might have a chance to break that cycle is worth celebrating in its own right. More than anything else, Britons are crying out for hope.

But, to judge from current campaign messaging, such celebrations may be short-lived. Labour, the Conservatives’ principal opponents, have gone out of their way to say that everything will change [PDF], but show that if—or more probably when—they achieve office, very little will. The plan, as far as it can be divined, is to keep voter expectations to an absolute minimum, so as to avoid a public opinion backlash if the country’s vital signs don’t improve. As I will show here, such a strategy cannot succeed.

Over the last year, Labour leader Keir Starmer has scrapped or watered down most of the major systems pledges he’d suggested were non-negotiable when he took over the party from Jeremy Corbyn in 2020. From reversing position on the free movement of people to and from the EU, to backtracking on raising taxes on top earners, to a healthcare policy that the Nuffield Trust has reported will be as bad for the NHS as the worst of Tory austerity, accusations abound that the Labour party of 2024 has more in common with Conservative party of David Cameron than even the centre-left Labour of Tony Blair. “My my, how the Overton window has shifted,” mutter bewildered pundits, implying that political tides are some wondrous phenomenon like the aurora borealis, rather what they are, which is a direct outcome of strategic political manoeuvring by specific actors.

Labour’s climate plans also appear to have been a victim of this shift, thanks in no small part to the dragging of climate action into Britain’s inane culture wars. Since backing away from its pledged £28 billion-per-year for green policies, Labour has been keen to regain the initiative. But as James Murray of BusinessGreen has summarised, the party’s climate manifesto is “deliberately light on details”. While some aspects of its plans on energy and the environment appear bold at a distance, innovations such as GB Energy, which was initially framed as a nationalised green power company, have been revealed by Starmer himself to be more of a public-private “investment vehicle” for energy projects. The enterprise will receive £8.3 billion of investments over five years—one whole parliamentary term—which, given the scale of the challenge at hand, is a paltry sum. Yet GB Energy is the only vaguely climate-adjacent policy on Starmer’s six-point “first steps for change” card.

This brings us to the underlying critical fault in 2024 Labour’s approach, which is this: from a strategic perspective, Labour has, either consciously or subconsciously, chosen to adopt the Conservatives’ fabricated passion projects as its own, along with a strictly Conservative conception of how politics and economics function. As a party, it has decided that the things the Tories have chosen to care about should be the things everyone should care about.

Take Rishi Sunak’s ludicrous talk of a “war on motorists”—a war that doesn’t exist, yet a totem designed to appeal specifically to the Irate Surrey Range Rover demographic. Labour has adopted that framing, with a daft, climate-deaf “Labour is on the side of drivers” campaign, while apparently backburning a laudable and climate-compatible commitment to nationalising the railways.

Then we come to the Tory red meat of immigration—a crisis of the government’s own making. Labour could choose to explain, as less fearful, less xenophobic parties have done, that the benefits of migration to the UK comprehensively massively outweigh any drawbacks. Instead, the party has adopted the Daily Mail’s language of “small boats” and “criminal gangs”, without explaining that the only evidence-based method for reducing illegal channel crossings is more legal pathways for migrants. The “criminal gangs” framing serves only to further infantile, violence-inducing xenophobia and small-islandism in a shrinking, warming world.

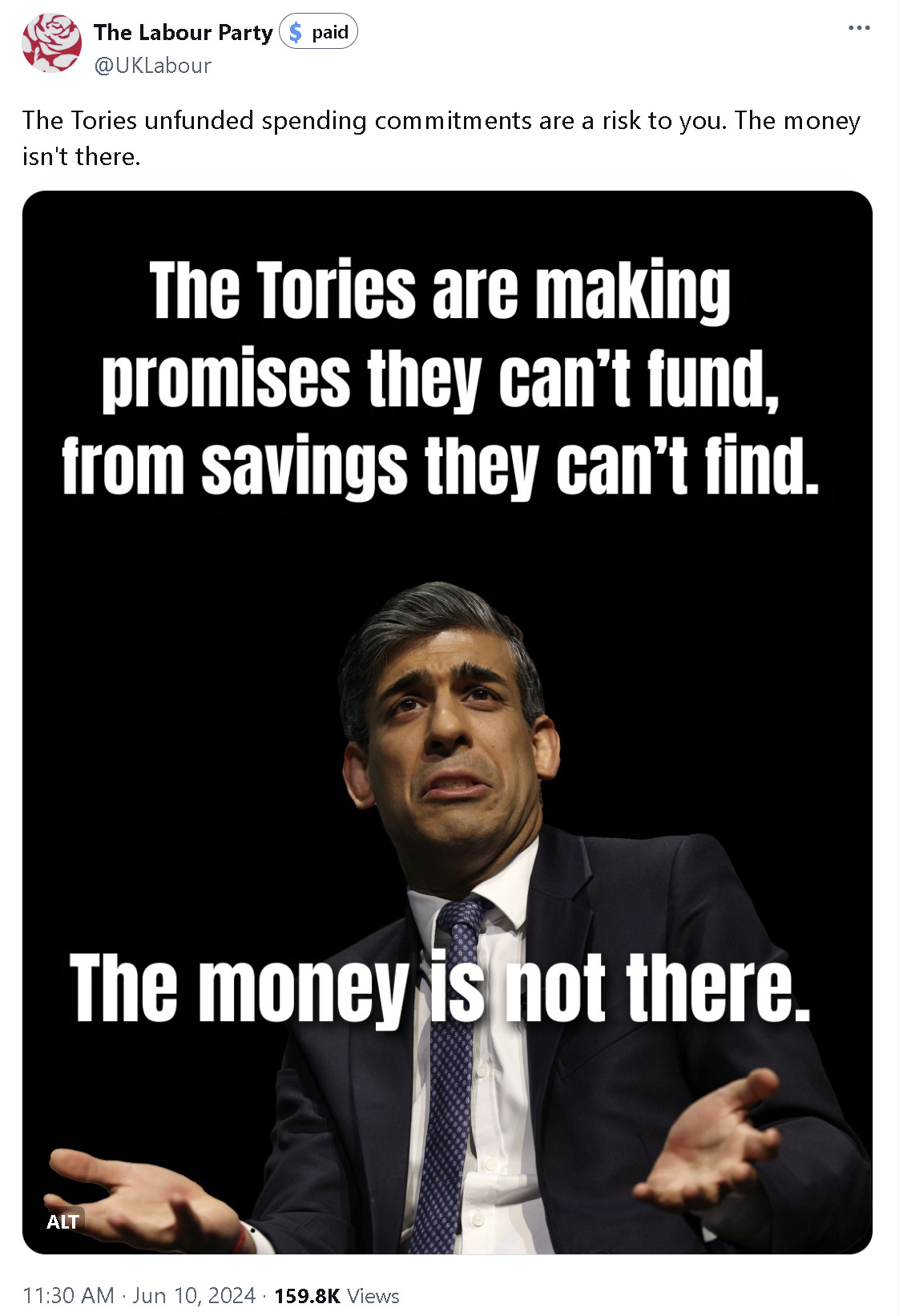

But perhaps nowhere is Labour’s adoption of Conservative tenets more starkly signalled than in the way it discusses economics. This is transmitted in its use of the slogan, repeated across social media by numerous would-be ministers, that:

‘The Money Is Not There’

Like a tagline from some downbeat, straight-to-video Jerry McGuire sequel, this phrase is being trotted out verbatim on both official and unofficial Labour channels. It is a staunchly neoliberal construct; a throwback to David Cameron’s austerity era, when in the name of “balancing the books”, government spending was stripped to the bone, and kept there.

It is also not, according to any rational interpretation, true.

As an economic plan, austerity was a catastrophe, leaving the country with crumbling schools, threadbare public services and literally bankrupt local councils. Beginning in 2010, austerity amplified the brutal impacts of the unforced error of Brexit (2016-) and the everything-everywhere shock of Covid (2020-), resulting in levels of depravation not seen since the Victorian era. Britain now lags the rich world in almost every social welfare and wellbeing metric. One particularly stark illustration of this rolling crisis is the rate of homelessness, which is rising faster in Britain than anywhere else.

And yet, for its cheerleaders, austerity was a ghastly success. As David Cameron himself indicated, the real point of austerity was not, as claimed, to reduce the deficit, but to achieve the long-desired Conservative ambition to permanently shrink the size and scope of government. Austerity, in real terms, means that far less money is now reaching low-income and vulnerable people, while the wealthiest in society are richer—far richer—than ever before. The policy prescriptions that achieved these objectives were in every sense deliberate; the outcomes have been, for many Conservatives, exactly what they wanted.

For everyone else, the tragedy of austerity is that it was wholly unnecessary. All the empirical evidence we have indicates that increasing spending would have delivered better outcomes across the board for regular British people.1 Both before and since 2010, the lie behind the claim that “the money is not there” has been revealed in practice. Quite apart from anything else, when the political class needs money “to be there”, it magically appears—see for example the UK’s eye-wateringly expensive Trident nuclear submarine upgrade, which is set to absorb so many billions of pounds, no one seems to be able to convincingly count them, but last year it added up to £8.1 billion.

There’s no mystery as to why this is the case. As economists such as Stephanie Kelton and Steve Keen have convincingly argued, state finances do not—indeed, must not—operate like those of a household, or a business. New economic thinkers have broken down the fact that governments have a range of options that, when applied correctly, generate significant, sustainable cashflows. They have shown, further, that almost all mainstream claims about the terrible harms of national deficits are false. Meanwhile, arguments that the assumptions of neoclassical economics make its equations unfit for purpose are being proven correct, in real time, by developments in the field of complexity economics.

In short, just as we discovered in the realms of medicine, biology and physics over the course of centuries, when it comes to economics, our original, primitive assumptions about how the world works were just that. We now know better.

Claiming that “the money isn’t there”, on the other hand, is to adopt the language and false premises of austerity. In political terms, it is simply an excuse for inaction; an attempt to set the bar of expectations for an incoming Labour government at limbo height. But people understand, intrinsically, that creating change costs money. From a systems perspective, expecting to achieve better-than-promised results from faulty premises is, at best, wishful thinking. Moreover, from a psychological perspective, it’s absolutely terrible for Britain’s future.

Ending The Downward Spiral

Physically and mentally, Britons are in a worse place than they have been in generations.2 Life expectancy is falling.3 Deaths of despair are rising.4 Under the circumstances, it’s hardly surprising that there’s more appetite for a change of political system in the UK than in any comparable European nation (with the exception of Croatia).5

The net effect of these realities is to engender a feeling of hopelessness: last year, a report from The New Britain Project think-tank indicated that Britons are deeply pessimistic about the nation’s current state and about the future, with 76% stating they feel the country is moving backwards.6

When a party claims there’s no money, it sends the unequivocal emotional message that “better things aren’t possible”. And, under the circumstances, that’s the last thing Britain needs to hear. Such a negative framing has implications for everything—not least climate change. That’s because the real threat to meaningful climate action is not climate denial, it’s ambivalence and apathy. To quote strategist Anat Shenker-Osorio: “our opposition is not the opposition, it’s cynicism. People believe our ideas are right. They just don’t believe that they’re possible.”

This is a desperately important message, and one that the Labour leadership would do well to ponder. A low-expectation population cannot be expected to envisage and work to create a more equitable, stronger and greener society. Sociological research indicates that low expectation-setting itself generates an effect sociologists call “learned helplessness”.7 Researcher Ryan Gunderson has shown that learned helplessness is “a social-structural and psychological phenomenon, rather than only a personal experience”, seeded by real, tangible events. The condition of learned helplessness reproduces to create a significant barrier between climate knowledge and climate action. “Why are alternatives to a system that drives climate change and other catastrophic risks still seen as unrealistic?” Gunderson writes. “We suffer from a political-economic system impervious to transformation before we suffer from a lack of alternative ideas.”8

This being the case, what should Labour do? After all, even the party’s more progressive policy planners would balk at the prospect of announcing that the national and global economy as it exists is based on a pack of false assumptions and misunderstandings about how the world works.

What a presumptive incoming party could choose to do, though, is point out how and why 14 years of Conservative leadership has caused such breakdown and immiseration. The predictable, reactionary choice would be to frame those 14 years as being characterized by incompetence—but that would be a mistake. The bold, above all accurate truth is that the parlous state of Britain today is not, at its root, a failed consequence of the corruption and incapability of individual men and women, but rather the result of a systematic Conservative ideology succeeding on its own terms. A party committed to a brighter future would seek to make this case, front and centre.

Labour may well win a decisive election victory in July. But what will it choose to do with such a mandate? Will it strive to alleviate Britons’ collective learned helplessness, daring to imagine a stronger, healthier, kinder nation? Or will it cleave to a strategy of low expectations, welded to the defunct ideology that has impoverished the planet and its people?

Sir Keir, the ball’s in your court.

Elsewhere in climate news …

Well, Elsewhere in climate news is on hiatus, but I was delighted/star-struck/chuffed last week to finally meet the incredible writer and climate communicator Mary Annaïse Heglar. In the space of a few months, Mary has released not one but two books: Troubled Waters, from Harper Muse, is a gorgeously written, beautifully poignant novel about two generations of Black women from the American US South and their struggle to heal in a world that is burning. The World Is Ours to Cherish, from Random House Kids, is a picture book that celebrates life and nature, and urges kids to band together to help the planet. Ideally you should buy one or both books from your local, independent, non-Amazon bookstore, but then go over to Amazon and leave a review, as that’ll help Mary shift more copies of these vital climate works.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4952125/#:~:text=The%20entire%20system%20rapidly%20unravelled,were%20by%20now%20inextricably%20entwined

https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/health-inequalities-lives-cut-short

https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/bulletins/nationallifetablesunitedkingdom/2020to2022

https://blog.policy.manchester.ac.uk/urban/2024/03/the-toll-of-deaths-of-despair-in-england/

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jun/25/britain-crises-hopelessness-market-towns-suburbs

https://www.newbritain.org.uk/_files/ugd/e2c59a_ea0c9802012949d2a86485c2b6187ce7.pdf

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140197197900889

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jtsb.12366